People often use the phrase “do not reinvent the wheel” to describe using an existing method towards a new task rather than creating one anew. Evolution tends to follow a similar philosophy. Many changes utilize genetic toolkits that have long been present, tucked away in the genome of the organism. Sometimes these toolkits have already been used repeatedly for various traits. The common fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), a model test subject for over a century, has been scrutinized in remarkable detail to gain an understanding of molecular interactions and evolution. When researchers discovered the NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway in mammals that functioned remarkably similar to the Toll pathway in Drosophila it was assumed that the immunological pathways were homologous (e.g. using the same toolkit).

The NF-kB pathway establishes its importance due to its swift reaction time. Most transcription factors are synthesized as needed. Building a protein from scratch then applying it where

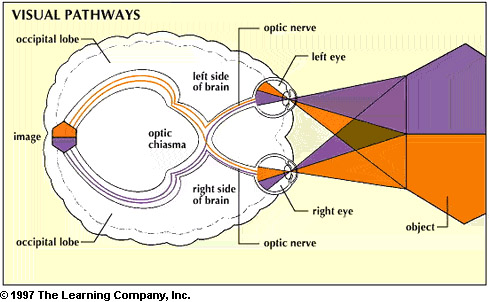

Figure 1: Contrasting transcription pathways between Drosophila and Mammals

needed takes a fair amount of time. Sometimes, like during a pathogenic invasion, the cell cannot survive long enough to produce these proteins. In the immune system these proteins can be constructed preemptively, bound, and inhibited in the cytosol for future use. The NF-kB pathway activates these stored proteins by cleaving the inhibiting molecule and thus allowing the transcription factor, NF-kB, to enter the nucleus. The Toll pathway operates, essentially, in the same fashion as NF-kB (Figure 1). However, Drosophila uses completely different proteins to ultimately provoke a similar immune response with Dorsal-related immunity factor (Dif ).

The Toll pathway plays another, yet significant role only found in Drosophila. After the egg is

Figure 2: The Toll-Dorsal Pathway in Drosophila melanogaster

fertilized it lays the foundation for the rest of development, ventral and dorsal (down and up). Upon fertilization, the ligand Spätzle (SPZ) is distributed across the perivitelline membrane (Figure 2a). From here, SPZ binds to the Toll receptors of cells maternally designated to become ventral. The Toll receptors set in motion a cascade that phosphorylates CACT (the inhibitor) which allows the transcription factor to promote the production of the protein Dorsal (Figure 2b).

These pathways were initially thought to have arisen from a common ancestor to both Drosophila and mammals. However, it seems this is only partially correct. Genomic research opened up new, previously unexplored areas to consider. This pathway did, initially, form in a Eumetazoan ancestor. This pathway was markedly underdeveloped and only contained a few components. When the bilateral lineage diverged into deuterostomes and protostomes the common pathway ended. From here, both NF-kB and Toll evolved independently through gene duplication.

These diverse differences between pathways give great insight to the evolutionary history of the circuit itself. In order to have diverged so far in composition yet retain similar function suggests the ancestral pathway to have been particularly modular. In other words, the ancestral pathway was constructed using multiple pieces (modules). This setup allows individual modules to be modified over time without removing the core process of the system. Drosophila slowly modified this pathway to affect larval development by introducing Dorsal and SPZ into the circuit. As a result, Drosophila is able to use a single genetic circuit for dual regulation.

In Biology, nothing is ever as simple as it appears to be. The subjects could range from immune response pathways and developmental regulation to simple autosomal point mutations, but more research is always needed. The NF-kB pathway was thought to be well known until just recently, yet new information radically altered our understanding of it. With additional research, who knows what we could uncover next?

Belvin, M. P., Anderson, K. V., 1996. A CONSERVED SIGNALING PATHWAY: The Drosophila Toll-Dorsal Pathway. Annual Review Cell Developmental Biology. 12, 396-416.

Lemaitre, B., 2004. The road to Toll. Nature Reviews Immunology. 4, 521-527.

Leulier, F., Lemaitre, B., 2008. Toll-like receptors — taking an evolutionary approach. Nature Reviews Genetics. 9, 165-178.

Waterhouse, R. M., Kriventseva, E. V., Meister, S., Xi, Z., Alvarez, K. S., Bartholomay, L. C., Barillas-Mury, C., Bian, G., Blandin, S., Christensen, B. M., Dong, Y., Jiang, H., Kanost, M. R., Koutsos, A. C., Levashina, E. A., Li, J., Ligoxygakis, P., MacCallum, R. M., Mayhew, G. F., Mendes, A., Michel, K., Osta, M. A., Paskewitz, S., Shin, S. W., Vlachou, D., Wang, L., Wei, W., Zheng, L., Zou, Z., Severson, D. W., Raikhel, A. S., Kafatos, F. C., Dimopoulos, G., Zdobnov, E. M., Christophides, G. K., 2007. Evolutionary Dynamics of Immune-Related Genes and Pathways in Disease-Vector Mosquitoes. Science. 316, 1738-1743.

So if the Giant Fibers end with the thoracic ganglion what happens next? The ganglion shoots the signal to the dorsal longitudinal muscle (DLM) and tergotrochanteral muscle (TTM or “jump muscles”). This moves two thing: the legs and the wings. What do the legs do? JUMP! Thus, the reason they’re called jump muscles. The wings do something a little more complex. Upon receiving a signal the wings go from the closed position to the open position and slightly elevate. So really the one nerve bundle initiates a double whammy of legs and wings. The strange part is that the TTM does both of these functions. The DLM is only indirectly involved.

So if the Giant Fibers end with the thoracic ganglion what happens next? The ganglion shoots the signal to the dorsal longitudinal muscle (DLM) and tergotrochanteral muscle (TTM or “jump muscles”). This moves two thing: the legs and the wings. What do the legs do? JUMP! Thus, the reason they’re called jump muscles. The wings do something a little more complex. Upon receiving a signal the wings go from the closed position to the open position and slightly elevate. So really the one nerve bundle initiates a double whammy of legs and wings. The strange part is that the TTM does both of these functions. The DLM is only indirectly involved.